Are capitalism and socialism at war? We often portray them as such. Yet within the world’s industrial economy it makes more sense to see them as deeply connected social priorities. Capitalism emphasizes individual wealth, hierarchy, growth, and elite accumulation of property; socialism emphasizes equality, group collaboration, and social welfare. These two constructs may be the Yin and Yang of the industrial world, but striking a balance between them is a challenge. Is it possible that “democracy”—that is, broad participation and compromise in public affairs—is the answer?

The contrasting priorities of hierarchy and sharing have existed as long as humans have spoken to each other. Ancient debates pitted hierarchical control of property against networks of social welfare; only gradually did chiefs and kings gain power over the collaboration of commoners.

Over time, as industrial society developed, institutions emerged to support both capitalist and socialist priorities. Capitalist institutions included industrial-scale production, corporations, global trade and empire, labor recruitment, and militarism. Socialist institutions included worker collaboration, trade unions, educational and health facilities, as well as movements to resist imperial conquest, oppressive wages and prices. And out of the same industrial crucible arose the ideas and practices of democracy.

Tensions grew worldwide during the nineteenth century. Capitalists gained control of politics in their homelands and then conquered most of the world. Socialism spread among workers in imperial homelands and overseas, as movements against slavery, conquest, and exploitation. Capital and labor—each challenging the other—became the two main foci of industrial society.

From 1800, a few European nations built industries, expanded their trade, and conquered most of Asia and Africa. Another new nation, the United States, traded profitably with other continents while also conquering North American lands and peoples, leaving many without rights. Meanwhile, socialist ideas rose among the farmers and workers who built the vessels, created the products, and carried the goods for trade.

Struggles between capitalist and socialist outlooks became steadily more antagonistic as the twentieth century opened, pairing worker-employer struggles with racial antagonism. Then came World War I, which killed millions and threatened to topple the great powers.

Capitalist vs. Socialist Worlds: 1920–1990

In a single empire, Russia, supporters of socialism took power and came to govern some seven percent of the world population. The Soviet Union proclaimed, “socialism in one country,” and within two decades built sufficient industry to survive Nazi Germany’s invasion in World War II. Postwar socialist movements arose, and by the 1970s, as many as 40 percent of the global population lived under socialist governments.

Capitalists and socialists each learned valuable lessons during these 70 years of antagonism. Socialist states faced military threats from capitalist powers, but also the need to adopt capitalist priorities, such as accumulating funds from citizens to invest in industry. As a consequence, socialist societies recognized trade unions yet prevented them from bargaining for wages. (Socialists in capitalist countries faced different problems. They were activists in trade unions and political parties and supported schools and pensions. But they could be charged with sedition for their beliefs.)

Capitalists, too, learned from the competition. They came to understand the need to make concessions to socialist priorities in wages, hours, pensions, and health care. The International Labor Organization formed to recognize trade unions and encourage pensions; Keynesian economic policy reduced unemployment by expanding national debt. Yet ideologically, for capitalists, socialism was considered subordinate and had to accept its subordination.

During this time, capitalist and socialist regimes each handled democracy badly, as shown in the analysis of historian James T. Kloppenberg. The homelands saw some participation in government, and the colonies remained dictatorships until new nations arose through decolonization. But dictatorial governments reversed citizen participation on every continent. Famine hit Soviet Russia and, later, China. World War II brought slaughter of civilians as well as combatants, especially under German and Japanese leadership.

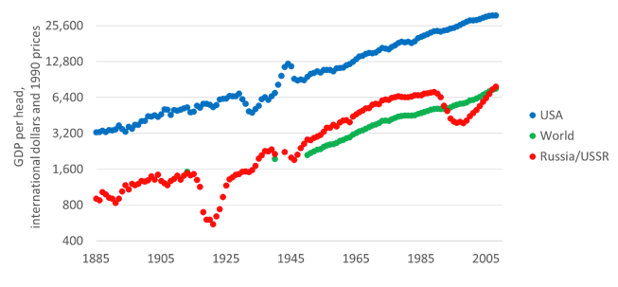

In economic growth, the USSR’s economic and technological growth exceeded that of the U.S. at some times. However, the U.S. ultimately prevailed.

Socialism and decolonization expanded in the 1970s, while economic growth slowed. Policies now known as “neoliberalism” took hold in capitalist states and international organizations. The IMF and World Bank successfully put severe economic pressure known as “structural adjustment” on ex-colonial and socialist countries. And socialist states in Europe and elsewhere, already buckling, collapsed in a wave of popular movements from 1989 to 1994.

Capitalism on Its Own: After 1990

As socialist governments fell, new regimes rapidly sold off most state-owned enterprises at low prices; they also revised labor contracts to reduce wages and pensions and cut back on public education and health. (Meanwhile, China showed another possibility, as it repressed public opposition to bureaucracy in 1989, expanded investment in industrial output, and created numerous private firms, most notably in banks.)

The global capitalist economy expanded in unexpected ways. Russia and, arguably, China, became capitalist economies. In textile production (always a central dimension of industrial output), Beijing took the lead: China became the largest exporter of clothing by 2000. In steel production, Japan passed the U.S. in output in the 1980s. And by 2020, it was China that produced over 50 percent of the world’s steel—some 95 percent of it from state-owned enterprises. Microelectronics industries, a great new source of profit, also came to be dominated by Asian capitalist firms. The U.S., however, claimed global communication platforms such as Facebook.

But the side of the economy relying on socialist priorities—especially in health and education—had different results. Most recently, the health industry has been shocked by pandemics, especially COVID-19. And because health investment has historically focused on profitable pharmaceuticals rather than preventative public health measures, a tragic number of lives—particularly in nursing homes and prisons—were lost. In education, levels of investment became highly unequal and led to wide disparities. In the triennial worldwide high school math tests in 2018, 20 nations had top scores, led by results from four Chinese provinces. Nearly five dozen other countries got lower scores, while 120 African, Asian, and island nations were unable to take the test at all.

And when problems in environmental degradation surfaced in the 1970s, both capitalist firms and socialist planners refused to pay the external costs of exploiting mines, waters, fish, and labor. To this day, corporations support environmental regulation only if it gives them profit. (The environment, since it is only a nuisance and not a priority in the capitalist agenda, has necessarily been adopted as a priority in the socialist agenda. Thus, today’s socialists must somehow balance concern for social welfare with protection of nature.)

Capitalist priorities have had the upper hand since 1800, and the supporters of capitalism have not changed their outlook since the Cold War. But, as I argued in a 2017 address, the facts have changed. First, one can no longer claim that free markets inevitably bring the highest productivity. China has disproved that argument in both the socialist and capitalist sectors of the economy. Second, one can no longer ignore the worldwide environmental crisis. And third, even the distinguished economist Branko Milanovic no longer claims that economic growth can resolve the crisis of social inequality.

So, what is the role of democracy in this ongoing struggle of competing outlooks? Can it be a tool to create a state of Yin and Yang? After all, the essence of democracy is compromise.

Humanity now faces environmental and social disaster, partly resulting from decades of capitalist dominance. In order to address these problems, a focus on social welfare and environmental sustainability must be renewed. Democracy could be a tool to acknowledge, analyze, and debate such priorities, and then perhaps create equilibrium between capitalist and socialist priorities—a balance of Yin and Yang.

The main point on capitalism and socialism is that the industrial economy requires policies for investment in finance and material goods (Yin) and for investment in human life, welfare, skills, and environmental protection (the expanded Yang). Going forward, we need to balance them better by considering social and natural welfare as primary goals and corporate profit as a secondary goal.

It’s true that these two agendas do not always fit together neatly. But any attempt to focus the industrial society only on capitalist priorities or only on socialist priorities will surely fail.

Dear Pat,

This is a wonderful essay. I will be using it in a course I am developing for high school students in civics, economics and ethics. Succinct and illuminating.

Best,

Susan

Truly brilliant, as expected!