Early Modern History, a subfield of World History, explores the centuries before 1800 CE. The Journal of Early Modern History, since 1997, has shown the importance of global interactions for the period from 1300 to 1800 CE. In addition, recent studies are expanding the scope of the “early modern” era to even earlier times, including the two books reviewed here: Anne Gerritsen’s The City of Blue and White and Ruth Mostern’s The Yellow River. Among others, a recent work on world history of science, edited by myself and Abigail Owen, reaches from 1000 to 1800 CE.

Stories from the Yellow River and Jingdezhen, an Early Modern Porcelain Center

The works of Mostern and Gerritsen show the detail that is known on the early modern economy, society, and ecology of China. Each author relies on an immense collection of written texts from imperial China, along with modern analyses. Both books focus on material reality, such as the great river valley and a famous type of ceramic ware, but also explore the topic through human interactions.

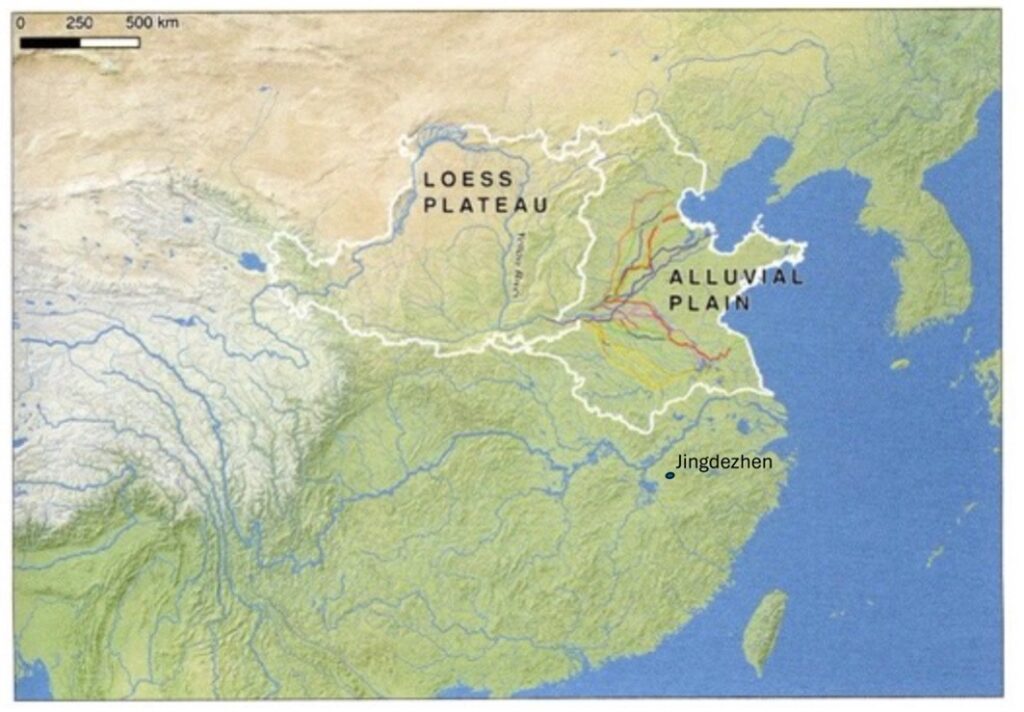

Ruth Mostern, setting out her spatial context, presents this map showing that the Yellow River begins in Tibet, flows around and through the Loess Plateau, then enters the Alluvial Plain, where the river’s successive courses have reached the sea. Mostern’s data, drawn from Chinese historical records, describe 3,754 events throughout the river’s watershed, spanning from about 200 BCE to 1900 CE. These events are grouped into 10 types of disasters (especially floods) and ten types of management of the river (especially building canals and levees). For example, the disasters of erosion created silt that made the river “yellow” and clogged the lower valleys starting in the 9th century; the alluvial plain lost population with the floods.

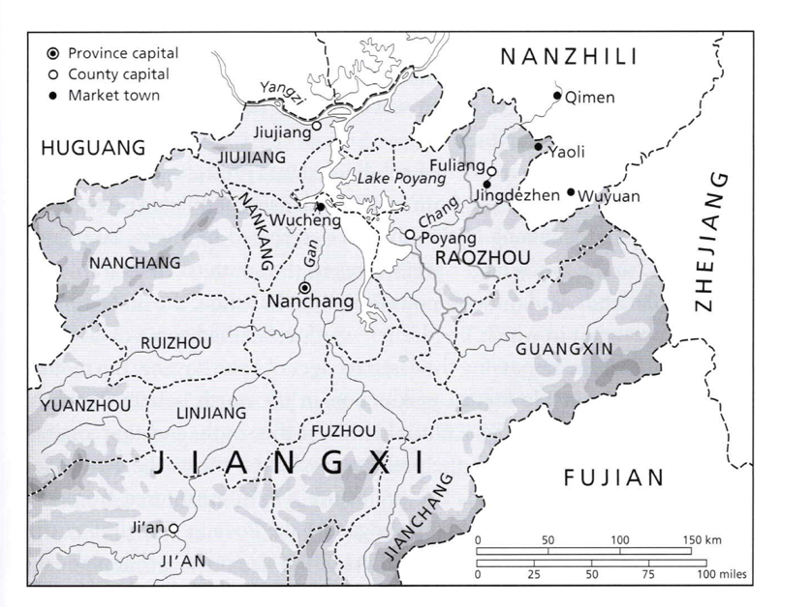

Anne Gerritsen tells a story of ceramics from 1000 to 1750 CE. Her map shows Raozhou prefecture, a subtropical region south of the Yangzi River. At top right is the city of Jingdezhen on the Chang River, downstream from the mountains, which provided artisans with clay and wood for modeling and firing in the kiln. Finished ceramics were sent down the Chang to Lake Poyang on the Gan River, to the Yangzi River, and then in all directions. At bottom left of the map is Jizhou (or Ji’an), another ceramics center.

Remarkably, both books identify a historical turning point at about 1350 CE. For the Yellow River, 1350 marks the shift from frequent, disastrous floods brought by war-induced erosion to an era dominated by attempts to manage the alluvial plain in the later period. For ceramics, 1350 brought a transition from regional exchanges of ceramic work to dramatic recognition of Jingdezhen-made ceramic ware in China and abroad.

The River Before 1350: The Rise of Yellow River Silting and Floods

The opening chapters of The Yellow River trace the earliest times, from the Holocene Optimum to a drying period, which began 5,000 years ago. From 200 BCE, thousands of events of the watershed are documented by time, place, and outcome—many floods but almost as many efforts to restrain the waters. The events are mapped and graphed to tell the story of the river.

This recent image shows two main aspects of change on the Loess Plateau. Huge amounts of labor built the terraces shown on the left, which expanded agricultural output. But the loss of foliage sped up erosion, as seen in the cliffs to the right. You can see in the smaller image that Loess is a rich, dusty soil formed in great areas of windblown soil.

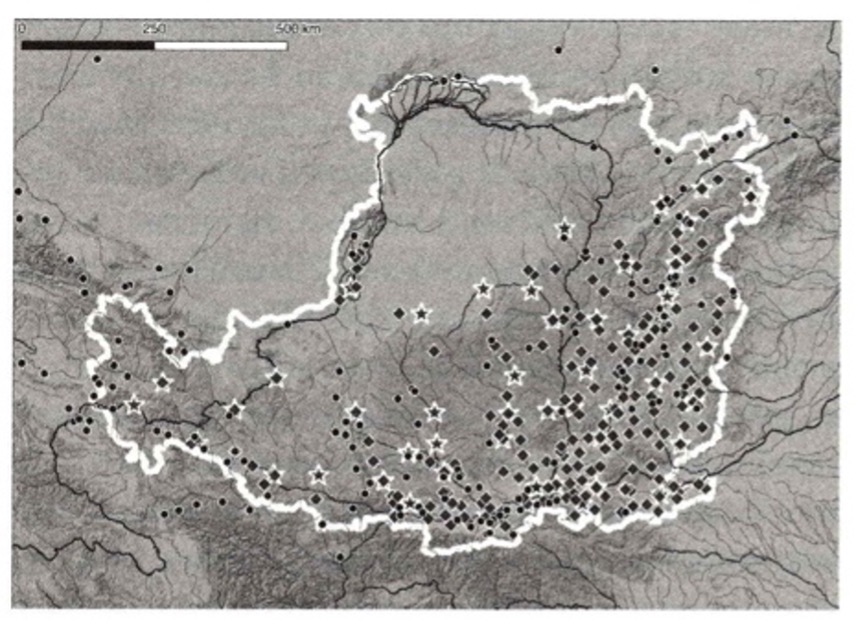

The lower-right, downriver section of this map of the Loess Plateau was the most densely populated region, brutally fought-over from 800 to 1300 CE. It was there that the most silt entered the river, to be later deposited in the alluvial plain, where it resulted in the floods and redirection of the river. Ouyang Xiu’s essays on flooding (1055) describe how warfare and settlement on the Loess Plateau caused erosion and downstream silt. But little effort went into halting the erosion.

Porcelain Before 1350: The Creation of Blue and White Porcelain

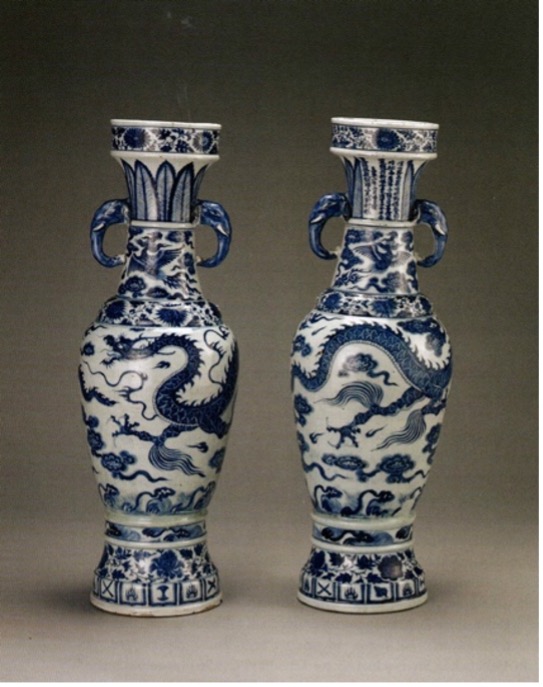

The city of Jingdezhen is believed to have existed as a center of ceramic production as early as 1000 CE; it gained early fame as certain wares were purchased by the emperor. But several other centers throughout China also prepared ceramic wares of varying designs. Gerritsen put great energy into clarifying the emergence of Jingdezhen’s distinctive blue and white ceramics. The photo below shows two remarkable examples of the mature blue and white artistry of Jingdezhen. These vases—known as the “David vases,” based on their modern English purchase— are dated 1351 and were donated to a north China temple.

Gerritsen traced every element of ceramic production: the clay, treatments of clay, the shapes and images selected, the glazes, the technique of painting under translucent glaze, the colors, the firing, and the consumer demand from the imperial court to purchasers both local and worldwide. Gerritsen—reading in multiple fields and topics—argues with subtlety that no one factor explains the rise of Jingdezhen. Instead, she emphasizes four main processes in her tale of Jingdezhen’s popularity.

When the Jin conquest of North China in 1127 drove the Song empire to the south, artisans from Cizhou in the north migrated to Jizhou to the south. This brought what became the signature technique of Jingdezhen ceramic ware—line drawing under glaze—further south.

Gerritsen also shows (at right) the decorative style developed in Jizhou during the 13th century, with leaves echoed on the David vases. Finally, she traces the purchase of cobalt mined in Central Asia, Germany, and China, to be used to reproduce the style of Jingdezhen ceramics (the blue color under the white glaze), sometime after 1300.

Porcelain After 1350: Blue and White Porcelain in World Trade

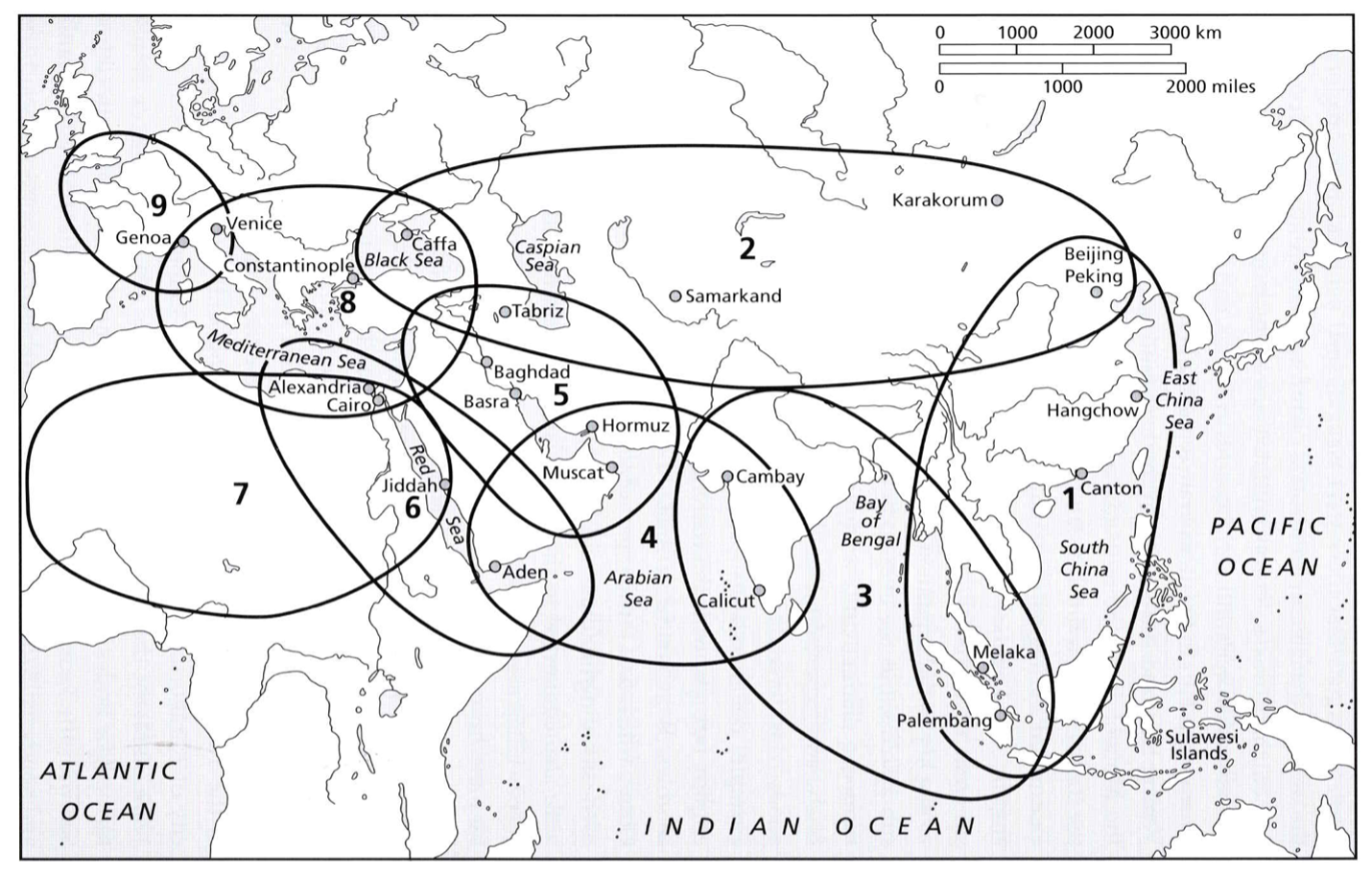

Gerritsen explores both the global and local movement of porcelain after 1350. First, she traces the expansion of export trade from Jingdezhen throughout Eurasia, as well as in China. This map (based on a 1989 original) shows overlap among regional trade circuits in the late 14th century. Gerritsen gives examples for each region but notes that Japan and Korea should have been included.

That is, the production of wares in Jingdezhen was adjusted to fit the interests of regional consumers, such as a dish in the form of Mount Fuji (pictured right) for purchasers in Japan. A 1323 shipwreck in Korea, in fact, contained large quantities of white Jingdezhen porcelain intended for Japan. Similarly, wares were specialized for regions of west Eurasia.

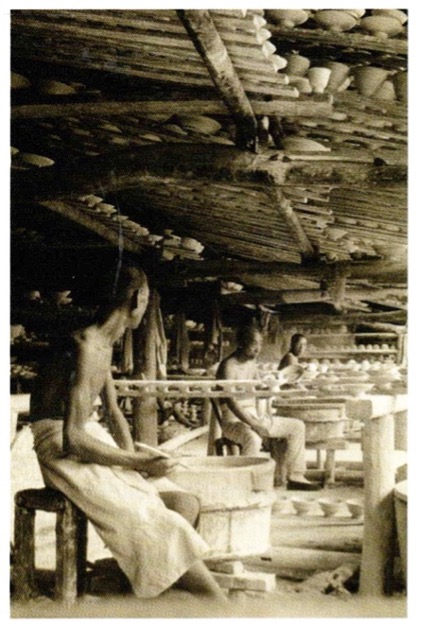

Gerritsen follows this global survey with a local analysis of the labor force, the structure of the factories, and the retrieval of clay and wood. She notes that travelers Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo each wrote about the process of clay preparation: burning clay with fern and then washing to whiten the porcelain. Beyond ceramics, separators were produced to protect the products while firing and during shipping.

International competition and eventual shrinkage of the market affected Jingdezhen’s ceramic industry—although production did continue. (See photo on the right, from 1920.) The beauty and the appreciation for the pieces, however, remains today. Thus, Gerritsen’s analysis points to details of eight centuries of production, finance, labor relations, export trade, the imperial court, and local sales.

The River After 1350: Disorder in China’s Alluvial Plain

This chart of events along the Yellow River (one of many in Mostern’s book) shows the post-1350 period, comparing annual disasters, management events, and the slow decline in moisture. After 1650, managerial work expanded significantly—almost entirely in the lower river.

Pan Yujin, a 15th-century Ming-era scholar and administrator, wrote a detailed manuscript on how to manage waterways. With it he drew an elaborate image (reproduced in Mostern, Figure 4.21, page 224) that shows rivers, sluices, dams, canals, reservoirs, and levees – each of them described in Pan’s text. These elaborate efforts helped to clear the Grand Canal of silt, but, like other such campaigns, failed to modify conditions upriver on the Plateau. Meanwhile the Yellow River itself continues to survive as the rains fall and the slopes direct its flows from Tibet to the Pacific.

Early Modern History Seen Through These Books

The City of Blue and White and The Yellow River show early modern China’s remarkable strength in technical and cultural knowledge, as well as its commercial links to the world. Further, the complexity and beauty of artwork and the centrality of water in history are reaffirmed memorably by Mostern and Gerritsen. And although China is shown to have been outstanding in this area, there were parallel centers of knowledge and culture on every continent from the 10th to 15th centuries.

Early modern history, so far, has been written mostly as comparisons of regions in their complexity. But it can also be global. These brilliant works show how: Mostern’s collection and analysis of data opens the door to global comparison of water management, and Gerritsen firmly links her regional study of production to global commercial and cultural change. Taken together, they successfully portray many aspects of early modern China with precision and subtlety, while also pointing unmistakably toward the global patterns of that age.

Dear Pat,

When I was in Thailand in the 1990s, I spent time at the kilns of Si Satchanalai (“under the cultural control of the Sukhothai kingdom”). I learned that production there followed monitored conditions in China. If pottery production was interrupted or reduced in China, the kilns immediately upped or even restarted their production between the 14th to 15th centuries. I used that often in classes as I had good pictures and, of course, they loved the transregional connection even without seeing Area 1 on Gerritson’s map.