Ethiopia’s royal conquests, buildings, written language, and devotion to the Christian faith—across several dynasties and over two millennia—make it stand out in African and world history. In many cases, however, Ethiopia is reduced to an example of global reach in the region. A closer look (from the bottom up) may reveal many unanswered—and unasked—questions.

What of the small ethnic groups that surround the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia? Did these groups create innovations and face great conflicts? What do we know about how they may have influenced the world today? Did they have a stable, unchanging existence? Did they lose their identity through absorption into the big kingdom? What is their story?

The stories of small ethnic groups can only be heard if others are listening for them.

To answer these questions and, more broadly, to make space for African History within World History, one must assume that significant historical change arises from small groups, not just large ones. As such, historians of Africa have learned to listen for the past voices of these small groups in order to preserve their stories.

For readers of history to hear past voices and to see the changes the speakers have made, these four steps must be satisfied: (1) deep in the past, people in small groups took innovative measures to change their world; (2) small groups preserved the memory of their adventures through song, dress, recitations, even written records—though some stories survive and some may be lost; (3) in recent times, scholars have recuperated these records, studied them, and translated their stories for others; (4) today’s readers of history must see the significance of these stories.

James Quirin, a skillful and fortunate historian, achieved all these steps in his new book, Historical Connections & Comparisons: Ethiopia & Pan-Africa in World History, which reveals lively histories of small ethnic groups in northwest Ethiopia, reaching back nearly a thousand years. Quirin focuses on the group known as Beta Israel (also as Falasha or Ayhud), a community of farmers and artisans living near the Ethiopian kingdom. Their religion relied on the Old Testament of the Bible, including a Saturday Sabbath. (Notably, they did not adopt the institutions of rabbinical Judaism, nor did they know Hebrew.) The Beta Israel were under regular pressure to submit to the kingdom and adopt Orthodox Christianity, especially as the kingdom expanded into their territory.

James Quirin, a skillful and fortunate historian, achieved all these steps in his new book, Historical Connections & Comparisons: Ethiopia & Pan-Africa in World History, which reveals lively histories of small ethnic groups in northwest Ethiopia, reaching back nearly a thousand years. Quirin focuses on the group known as Beta Israel (also as Falasha or Ayhud), a community of farmers and artisans living near the Ethiopian kingdom. Their religion relied on the Old Testament of the Bible, including a Saturday Sabbath. (Notably, they did not adopt the institutions of rabbinical Judaism, nor did they know Hebrew.) The Beta Israel were under regular pressure to submit to the kingdom and adopt Orthodox Christianity, especially as the kingdom expanded into their territory.

Quirin reviews oral traditions, cultural practices, and written records about the Beta Israel, showcasing centuries of celebration of their ethnicity—and how they harnessed energy, imagination, and determination to preserve and adapt their identity. In Quirin’s text, readers not only learn about their stories, but also how those stories were passed on.

When Historians and Communities Meet

The historian plays the role of reaching back in time, looking for historical remnants. Quirin, for example—in his lifetime of analyzing Ethiopian history—has adopted the perspectives of successive ethnic groups. Starting by reading in libraries and later visiting present-day communities, he looked for stories on ethnic groups and their social conditions. This led to his understanding of the various scales of Ethiopian life, including how households, occupations, ethnicities, and class distinguished the lives of landless people.

Historical communities, on the other hand, play the role of reaching forward. Before historians can ever uncover their stories, communities build memories by reaffirming identities, celebrating occupations, and carrying forth the names and exploits of their leaders. They leave markers of choices and outcomes, including migrations and social roles. Dress and religion, in addition to fireside talks, also become part of their messages for later generations.

The interactions of historians and past communities can yield a texture of historical perspectives and processes. For instance, Quirin was able to clarify how the Beta Israel maintained their own identity while resisting pressures for incorporation into the Ethiopian kingdom. In one story, the monk Simon of the Beta Israel forcefully debated with the head of the large and powerful Ethiopian Orthodox Church on the Trinity and the Godhead. This case prompted Quirin to ask, “Isn’t this perhaps another example of the important and inspiring story of how a people have sought a sense of self-identity against enormous odds?”

The Power of the Written Word

The analysis of oral tradition is strengthened when oral testimony can be confirmed by written documents (although written documents are sometimes based on earlier oral accounts). One chapter of Quirin’s book compares the Beta Israel and the Kemant, two closely related Agaw-speaking groups, both following the Saturday Sabbath, who faced pressures from each other and from the expanding Ethiopian state. Up to the nineteenth century, the Kemant acquiesced to the empire and emphasized rural agriculture, while the Beta Israel maintained their independence and increasingly became artisans as they lost their lands.

Quirin also traces the history of the Zalan, an ethnic group specialized in herding, showing how the community became dispersed in the twentieth century as its herding function came to be divided among other ethnicities. These stories convey a sophisticated view of the world at multiple levels, showing the importance of Ethiopian history to understanding both local and global history.

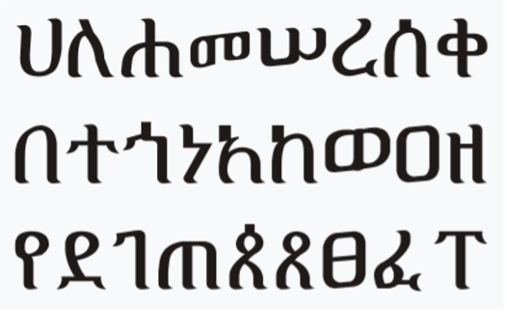

Written documents, often thought to be scarce in Africa, exist significantly for Ethiopia. They were first written in Ge’ez (shown below), an Ethio-Semitic language and script. The language, which had long existed, was written beginning in the first millennium BCE, using a Sabic script also used in South Arabia. With the adoption of Orthodox Christianity during the long reign of Aksum’s King Ezama, a language reform added vowels to each consonant and reversed the order of reading to left-to-right. The revised script is used today in many Ethiopian languages.

One outstanding set of written records includes 524 Christian prayers—in Ge’ez and Amharic, most likely of Amhara people—that were inserted into manuscripts from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. They had been catalogued by philologist Getatchew Haile. Quirin categorized these prayers as spiritual, human, and natural in scope, as they focused on one’s self, family, and enemies; the use of charms to fulfil hopes or repel evil; and a fear of disease.

Lessons from the Beta Israel Story

The Beta Israel maintained but also adapted their existence, culture, and outlook through a wide range of experiences and challenges. Over centuries, other ethnic groups have done the same, defending themselves in the shadow of centralizing powers seeking to absorb them. More recently, ethnicities are working to survive and coexist with the national states that replaced empires in the past century. In nations within the Arctic, the Americas, Australia, and Africa, indigenous peoples are gaining international recognition and new rights.

The experience of the Beta Israel changed gradually in the twentieth century as foreign Jews trained Beta Israel teachers in rabbinical Judaism and Hebrew so they could teach the community. These influences eventually led to the mass migration of almost all the community to Israel in 1985 and 1991—after the Israeli rabbis accepted that they had the “right of return.” Today, the Beta Israel are known as the Ethiopian Jews in Israel, or just as the Ethiopians.

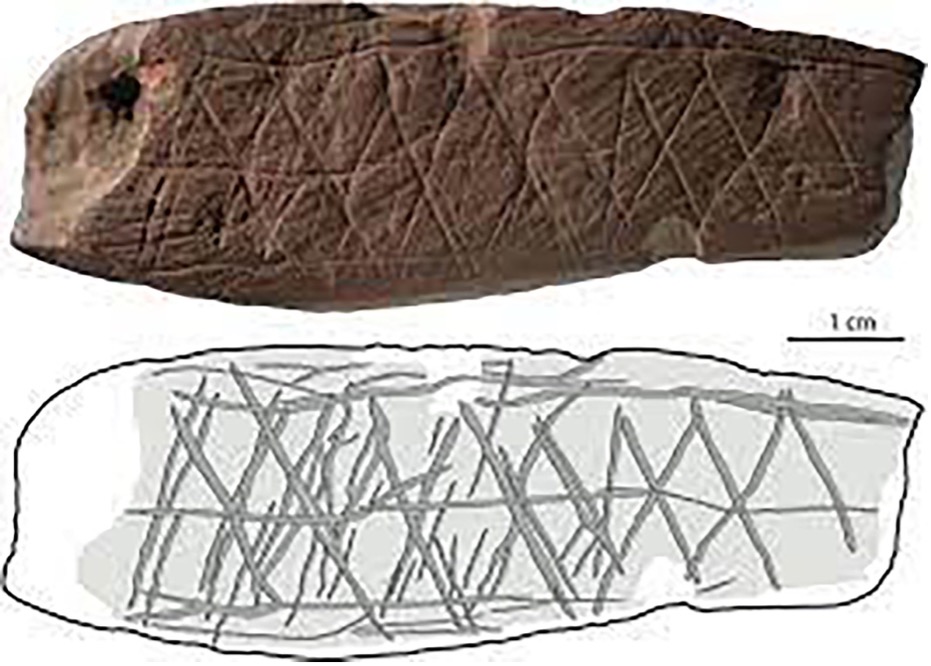

These perspectives on ethnic groups are not just new facts. They are the product of interactions between historians and past communities—and they will grow in number as historians apply new methods and deeper perception to uncover the stories of past groups. For example, in recent years, a spectacular new message has appeared in the discovery of a stone from Blombos Cave in South Africa. The etchings, made by a person or group some 70,000 years ago, show the organized thinking of the creator and the desire to leave a record for a later time.

We can see how Quirin’s approach, long prominent in the study of African history, is now beginning to prevail more broadly in world history—highlighting the flexibility of change over time with the integrated study of various scales, time-frames, social organizations, contending perspectives.

Thus, Quirin may be leading more people to examine history from the bottom up—that is, starting one’s analysis with small social groups and shorter time periods before expanding to the more general. Above all else, this approach—one I advocate for—values people and their lived experiences. On this point, I will give Quirin the last word:

Respect must be built upon a foundation that goes beyond mere tolerance and co-existence, but puts a positive valuation on all groups and peoples, and their histories and values. Such a view would accept the equal worth of each group and each individual human being.