New research is showing that the human occupation of the Americas took place much earlier than previously thought—and that it included unexpected, exciting adventures. This blog post provides a summary, but students and teachers of human history can trace the adventures of early Americans using web and GIS links to further track their movements along the oceans and across the continents.

Evidence of North America’s Earliest Humans: Footprints Lead the Way

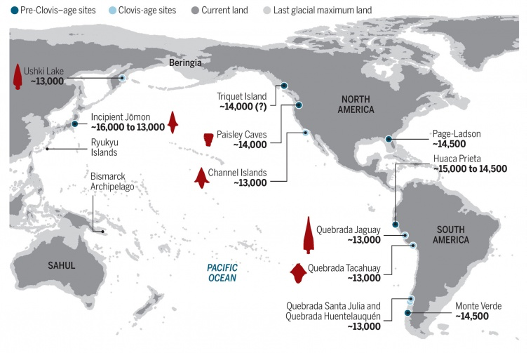

In the most extraordinary recent discovery, footprints of human boys were found, beautifully preserved, in White Sands National Park of New Mexico. They are dated to 22,000 years ago—almost 10,000 years before the Clovis spear tips of North America that were once thought to be the earliest human remains of the Americas. Other evidence suggests that the ancestors of these boys reached the Pacific Coast by watercraft, perhaps several hundred years earlier.

The original boats used by the migrants have not survived, but we know that they were constructed from animal skins stretched and sewn over wooden frames—a process still used today to make kayaks in the Arctic. The early settlers of northeast Asia and the Americas found great numbers of large animals, enabling them to build these skin boats for rivers and the sea. When the large animals died out, due to both hunting and climate change, settlers had to adapt. For example, they (especially the Algonquin people) built canoes from the bark of North American trees instead of animal skin.

Up until the eighteenth century, the Pacific coast from British Columbia to California remained the most densely populated area of North America. Salmon—both fresh and dried—provided ample nourishment for the settlers. When Canada was still covered by a sheet of ice, early migrants went inland, up the Columbia River and then down the Missouri River, ultimately settling in eastern North America. Other settlers moved inland from California through New Mexico and to the Gulf Coast, including the boys whose footprints would later be discovered in White Sands National Park.

Those with watercraft moved along the Pacific coast, settling in Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and the south of Chile, to the site of Monte Verde, which dates back 14,000 to 18,000 years ago. Those in Mexico and Peru climbed up to the productive highlands of the Sierra Nevada and into the Andes mountains.

Marine archaeologist Jon Erlandson led in showing how it was possible for people to travel the Pacific littoral some 20,000 years ago. When doing so, they relied on navigation skills and the plant and animal resources from the “kelp highway.” Notably, sea level was almost 100 meters lower in those days than today, because so much water had been consumed by the cold and deposited in sheets of northern ice. Today, underwater archaeology seeks to find more evidence on these early migrants.

Deeper Insights into the Lives of Early Settlers

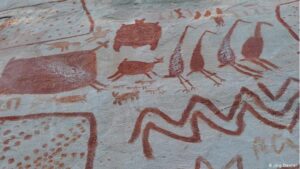

In Colombia, many settled along the coast. But some found a route to inland areas. A lowland opening in the Andes allowed settlers to spread into the two great valleys of the Amazon and the Orinoco. A key site on this route, Serrania La Lindosa, facilitated travel and offered a place for settlers to reflect on their journeys.

At Serrania La Lindosa, the cliffs arising from the river valley provided a great stone canvas—11 kilometers long—for a remarkable artistic monument to this migration. Some of the paintings on this canvas appear to have been created around the same time that the Clovis stone spear tips were created in North America. Further, as Erlandson has shown, this was a time when rather similar stone implements were created around the Pacific from Japan to Chile.

Languages of the Americas give clear indications of the major subgroups that formed among settlers, as well as the migrations that took place over time. Quite a different group of settlers, known as Na-Dene by their languages, arrived via the “kelp highway” from a different Asian community. They settled later and further north than the Amerind-speakers.

Thanks to academic research and to indigenous communities that share their knowledge, there is ample documentation of the lives of early Americans. And as this documentation grows, we gain a clearer understanding of the variety and innovation of early settlers throughout the hemisphere.

After 1492, innovation continued as people from other continents came to the Americas. But this also led to two great tragedies unfolding: the spread of disease caused a great decline in population, and the colonial rule of European powers brought more war and oppression than it did peaceful interchange.

Today, however, the indigenous peoples of the Americas are confirming that they are still here, establishing their political and social rights. The importance of their history is being recognized in their communities and among their fellow citizens.

Thanks to reader Chris Chase-Dunn for writing to remind me of the new book on this topic: Jennifer Raff’s Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas (New York: Twelve, 2022). It has been widely reviewed, for instance in New York Times (March 11, 2022) and by Elizabeth Weiss in Quillette (quillette.com, April 3, 2022).